Should leadership distribute authority and provide teams with a high level of autonomy to innovate, or should it centralize authority to prevent a proliferation of products and markets. The debate seems to be shifting toward distributed authority, however, what about SONY? The innovation powerhouse failed completely with the Digital Walkman.

Internal Competition

Alfred Sloan, the former CEO of General Motors, once divided the company into separate divisions, based on competing brands: Pontiac partially overlapped with Buick as well as with Chevrolet, etc. Back in 1931, Procter & Gamble introduced brand-managers, encouraging brands to compete with each other. P&G was convinced that internal competition compensated for the lack of flexibility and agility caused by the formal internal structure. In general, during the eighties and nineties, management theory supported the idea to grant divisional managers and brand managers a high level of autonomy to drive innovation and internal competition.

Dividing the Organization

By dividing the organization into agile, mutually-competitive units, silos began to take shape, leading to disconnected teams that were loyal to the divisional or brand management while employees became disconnected from the larger corporation. By additionally applying the scientific management theory to non-production processes ─ a theory characterized by specialization and the division of labor ─ the division of the organization trickled down to the level of functions, causing functional teams to become isolated while some even believed other teams were opposing a threat to what they aimed to achieve.

Disengagement

While divisional partitioning may have brought increased ‘flexibility and agility’, leading up to more valuable products as suggested by P&G, functional partitioning, or siloization, began to counteract the benefits of separate divisions and separate brand management teams. Simply because functional teams should not be competing with each other: they need to collaborate, in sequence, as part of the corporate value chain. This is the moment that functional silos began to cause problems. Similar to how rigid compartmentalization and departmentalization led to worker disengagement on the factory floor, as identified by Richardo Semler in 1995.

The Silo Effect

When Gillian Tett looked at the consequences of siloization in The Silo Effect, she described a case in which SONY had introduced the digital Walkman. Following the success of the Walkman, SONY was generally expected to create a digital successor. However, in 1999, SONY did not just launch one but three different, non-compatible digital Walkmans; each one created independently by one of its divisions. Customers got confused and sales were very disappointing. Tett blamed the silo-structure to cause the company to fail in its mission. Two years later, Apple announced the iPod and destroyed SONY’s hegemony in wearable music devices; almost in a heartbeat.

Good or Bad?

Gillian was right to blame SONY’s siloed structure because customers did not understand the reasoning behind the three different approaches, creating confusion and debate. While internal competition may lead to better products and more profit, SONY should have validated the various product innovations and then picked the one to go to market with. Instead, it relied on the customer to figure out which product was best. The launch was an error of judgment with huge ramifications.

However, we also discussed that distributing authority to drive innovation and internal competition can be really beneficial, thereby proving Tett wrong. So, what causes these contradicting outcomes?

Everything can be Disrupted

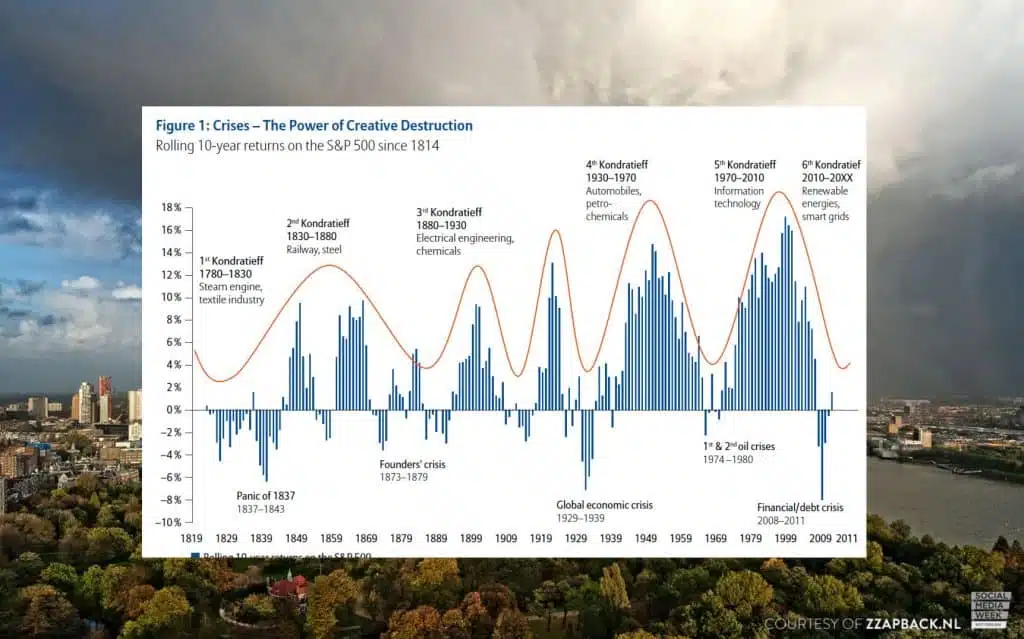

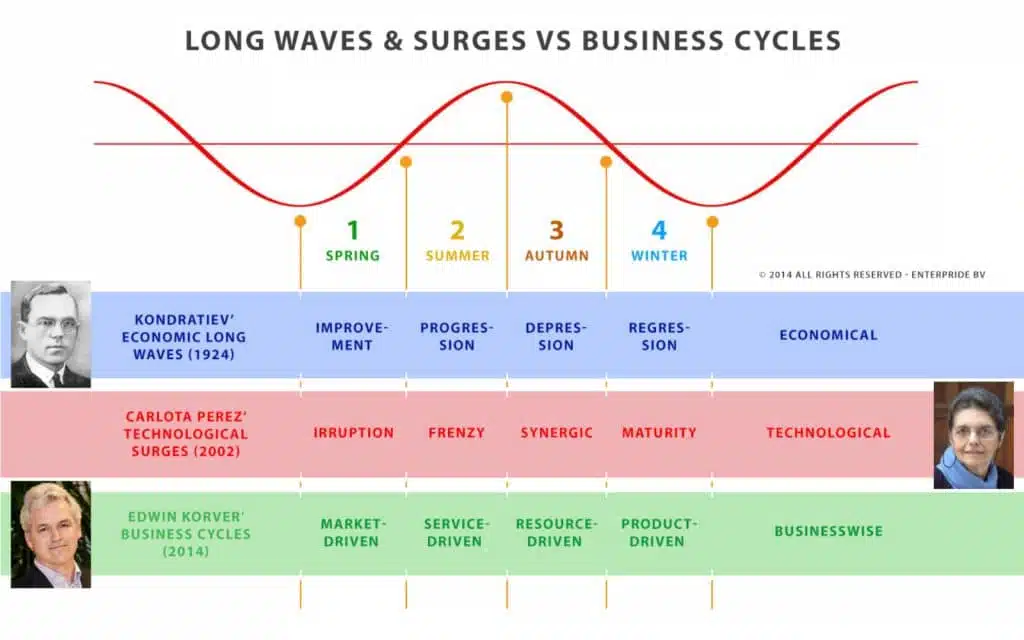

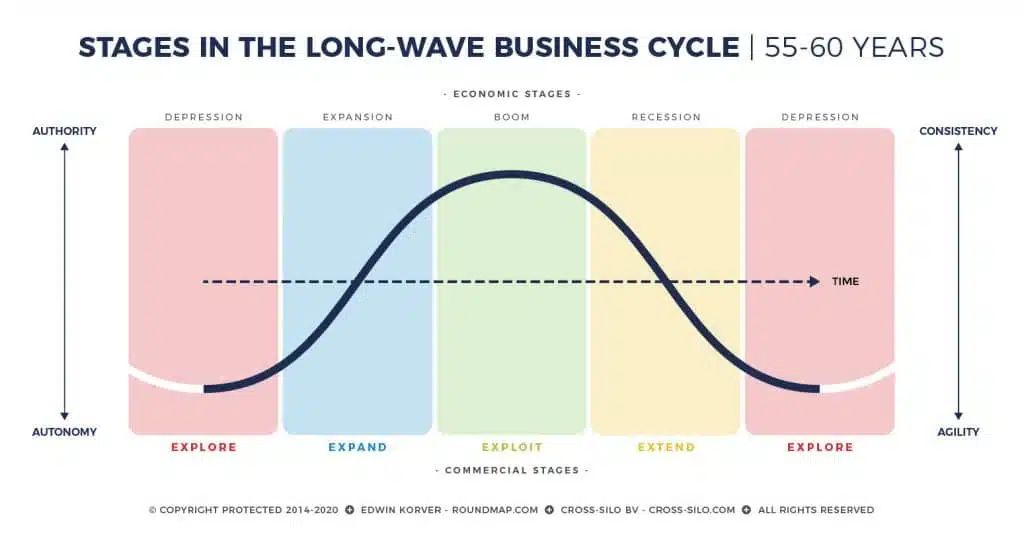

In 2014, I gave a keynote presentation on Social Media Week in Rotterdam. I decided to point at a pattern, known as business cycles in economics, to explain what I believed caused the disruptions most companies were facing and still need to face. I looked at two interpretations of business cycles: one created by Nikolai Kondratieff and the other by Carlotta Perez. Without going into too much detail: both economists described a long-term recurring pattern of economic growth and contraction, stretching over a period of 55-60 years while dividing each cycle into four stages. Their research confirmed, as suggested by the renowned economist Joseph Schumpeter, that the state of technology, to a large extent, determines the state of economic growth.

Redistributing Wealth

In the past 25 years, we’ve adopted entirely new ways of communicating, collaborating, and competing with each other, using advanced technology such as the internet, e-mail, social networks, mobile apps, and smart sensors. Those that dared to take the leap, by quickly adopting the technological advancements, soon began to disrupt those that (were forced to) lag behind. Google, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Facebook combined are now worth over 5 trillion USD, almost a quarter of the S&P 500 index. So, there should be no doubt that early-adopting new technology has a huge impact on how economic value is being generated and how wealth is being redistributed; from the old economy to the new.

Four Stages

Back to my presentation at Social Media Week. Kondratieff was an agricultural economist and, therefore, divided the long-term business cycle, or K-wave as it was called, into four growth seasons: spring, summer, autumn, and winter. Perez used a more technological nomenclature and named the four stages: irruption, frenzy, synergic, and maturity. I took a ‘businesswise’ standpoint and applied the terms market-driven, service-driven, resource-driven, and product-driven to the successive stages. Whether these labels are correct or not, it was the first time that I perceived an economy ─ as well as a business ─ to go through four stages of growth and decline, pretty much how a product lifecycle performs naturally (See: ROUNDMAP).

Technology-driven

Kondratieff, Perez, and I included, all pointed to how the application and adoption of new technology built up to create a new wave of economic growth. At first nibbling at the hegemony of the old wave representatives but once it gained traction, started to cause havoc among incumbents that failed to adopt the new technology. Kondratieff named at the growth-stages ‘improvement’ and ‘progression’, however, during this period much of the old-wave systems, structures, products, companies, and jobs get destroyed. The good news is that the new systems, structures, etc. that emerge from the new wave typically outweigh the numbers that are destroyed. But before that happens, the economy has to go through a crisis (crisis = moment of shifting, do or die).

Current State

We’re currently in the early stages of a new long-term business cycle: the ‘improvement’ or ‘irruption’ stage. The crises of 2008 marked the ‘maturity’ of the previous business cycle. Corona is a vital trigger-event that expedites the moment of shifting, destroying jobs at a high rate, driving companies to bankruptcy. All this to make room for the new order. Digitalization and robotization will diminish the effect of human labor on the marginal cost of a product, reducing the need for cheap-labor abroad, allowing businesses to shrink the supply chains, thereby removing risky external interdependencies. As mentioned before, this period is also marked by a shift of capital on the stock exchanges, from the old to the new wave representatives.

Businesswise

Although I believe I was right to label the four stages in terms of what drives the business at any given stage of the business cycle, I’ve come to realize that the labels need to be altered.

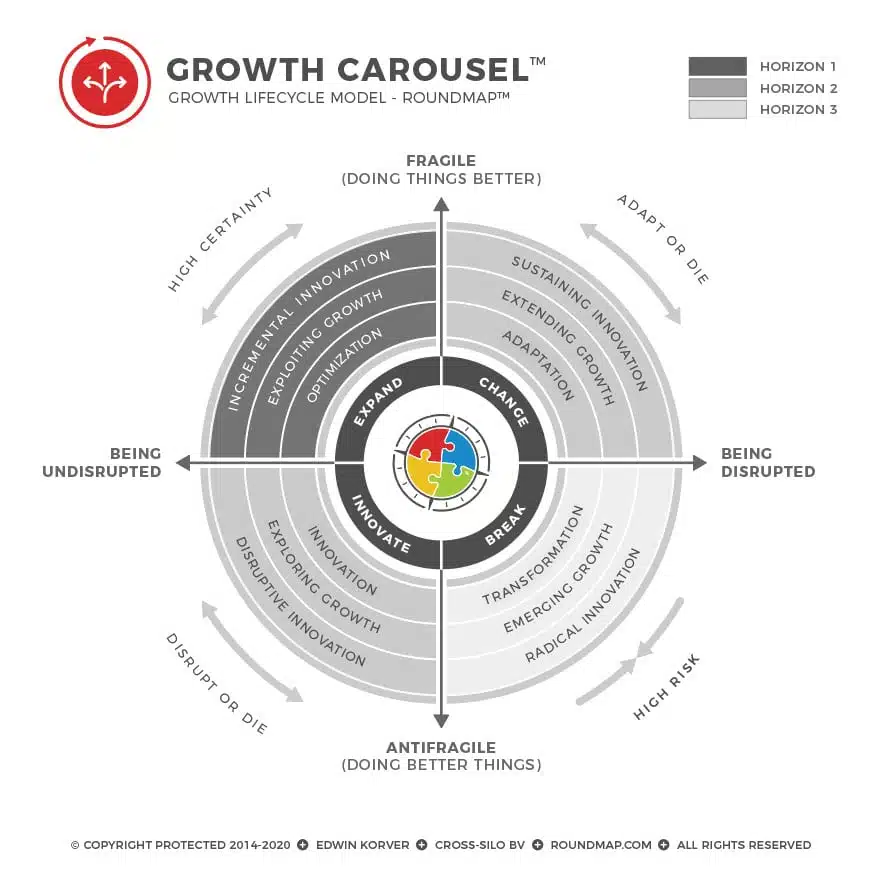

I’m now suggesting to consider the following sequence:

- Explore – Transform; Experiment; Disrupt or die.

- Expand – Grow share; Upscale; Grow or Die.

- Exploit – Incremental innovation; Optimize or die.

- Extend – Sustain; Defend; Improve; Economize or die.

Big Question

Let’s answer the question we’ve asked before: What causes these contradicting outcomes?

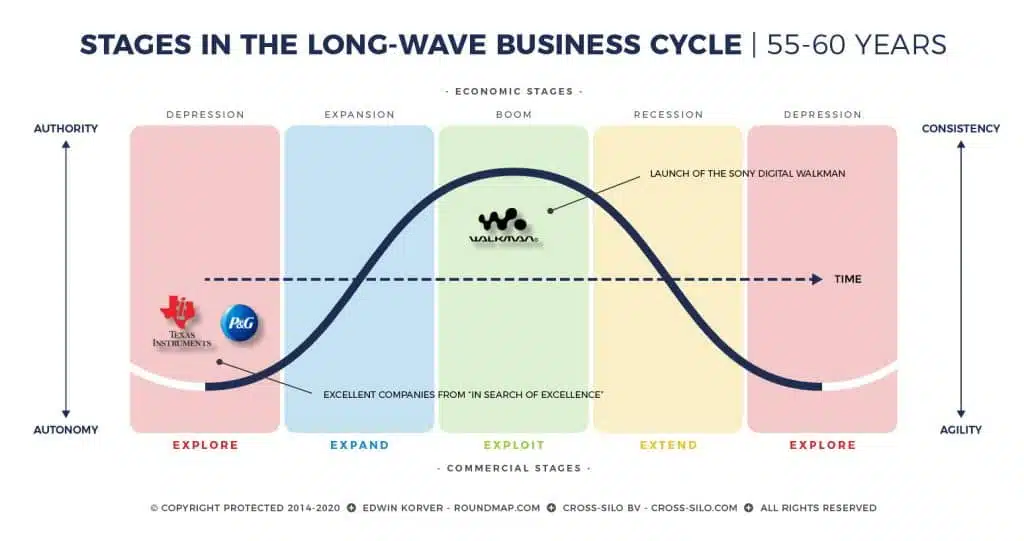

Case: SONY

In 1999, when SONY launched the three variations of the digital Walkman, the business cycle was at its peak. Customers were eager to adopt MP3 music players while (movies, games, software, and music) piracy was rising, inspiring websites like The Pirate Bay (2003). All SONY had to do was to provide them with a good-enough product. However, SONY was still in an Explore-state, based on distributed authority and internal competition to drive disruptive innovation. What it should have done was to centralize product development and drive incremental innovation. SONY’s mindset was aimed at breaking the cycle and so they did. In short: SONY was optimized for stage 1, exploration, but not for stage 2, exploitation. The silo culture worked against them.

Case: IBM/HP/TI

However, when two McKinsey consultants, Peters and Waterman, published In Search of Excellence in 1982, following a 10-year study, the US was still amidst an economic crisis. The authors had found that companies that outperformed their peers had to a large degree distributed authority across the organization, allowing small teams to create new products while forcing each team to compete with another over budget. Independent teams, siloed or not, drove innovation and helped these companies thrive. Was Tett wrong to believe that silos stifle innovation?

In fact, the modus operandi of these ‘excellent’ companies was so agile, that it inspired employees to start up their own businesses, giving rise to what Steve Blank and Eric Ries would later deem as the Lean Startup Method. As such, the method did not originate from Silicon Valley startups, it was simply mimicked from large enterprises like IBM, Hewlett-Packard, Texas Instruments, Procter & Gamble, and many others.

Authority versus Autonomy

No, Gillian Tett wasn’t wrong, she spoke in general terms while she should have looked at the business situation, i.e., the relative position in the business cycle. In general, every stage of the business cycle has its own characteristics and companies are well-advised to understand at what stage the business cycle is. If the cycle is at its peak, aspects like quality, continuity, reliability, service, and efficiency should be of main concern, requiring centralized authority to prevent uncontrolled outbreaks of risky variations in product lines and markets.

When the cycle is at the bottom and revenue streams become disrupted, leadership should step in, revise their vision of the future, distribute authority, provide leeway to small teams to experiment, and drive innovation. Despite the risks and costs involved, the leap forward, leaving behind the comfort and confidence of the old cycle, will be one of the biggest challenges the company will ever have to face.

Let’s apply this to the scheme:

Resume

Timing is everything in a business cycle. However, it makes no sense to suggest that if SONY had launched the digital Walkman in an earlier stage things may have gone another way, because we don’t know. But there is such a thing as Kaufman’s adjacent possible: the digital Walkman wasn’t possible earlier on in the cycle.

Growth Carousel™

ROUNDMAP’s Growth Carousel™, one of five models incorporated in the business framework, also incorporates the four stages of the business cycle: